Special Prosecutors

What is a Special Prosecutor?

These guys have a lot of names: special prosecutor, independent prosecutor, special counsel, independent counsel. They all mean roughly the same thing, a lawyer who is appointed to investigate something where the normal investigation agency has a conflict of interest. The highest profile ones are when the President might have done something wrong and it would be weird for the Justice Department to investigate their boss. So the Attorney General (with the President’s blessing, because it would look real shady if they said no) appoints somebody to investigate independently.

An independent prosecutor usually has a narrow scope of investigation, which has in the past evolved to include other crimes they uncover. Now, it is more common for them to pass on information to the FBI or other Justice Department agencies if they learn about crimes that are outside of the scope of their investigation. At the end of an investigation, the special prosecutor makes a recommendation for future prosecution or legislative action, and submits these along with a classified report to the Attorney General who then decides what information (if any) is released to Congress and the public.

Okay great. And what exactly is the Justice Department?

The Justice Department (aka the Department of Justice or the DOJ if you’re really cool) is part of the Executive Branch of government and it’s headed by the Attorney General. The DOJ is in a club of 15 departments like the State Department, the Department of Defense, the Department of Energy, and the Department of Education. All of those departments and cabinet positions you hear about when there’s a new president. Most of the heads of those departments have titles that start with “Secretary of” except for the Attorney General (and the Postmaster General who they kicked out of the club.)

The Department of Justice is in charge of federal law enforcement agencies including the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI), Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA), the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms, and Explosives (ATF), and the Federal Bureau of Prisons (BOP).

Ethics in Government Act

After Watergate, Congress decided to pass a law to regulate how special prosecutors would be appointed (and fired.) Title VI of the Ethics of Government Act was called the Special Prosecutor Act, which created the Office of the Special Counsel within the Department of Justice. While the Attorney General kept the authority to decide the need for a special prosecutor, the appointment would be made by a three-judge panel, and they could only be fired for wrongdoing or incapacitation. After 1983, the law was amended and renamed the Independent Counsel Act and extended until 1992 when it lapsed, was renewed in 1994 (in time for Kenneth Starr to be appointed) and allowed to expire in 1999 (because the Starr investigation went a little nuts.)

The Ethics in Government Act also included requirements that government officials file financial disclosure forms “which include the sources and amounts of income, gifts, reimbursements, the identity and approximate value of property held and liabilities owed, transactions in property, commodities, and securities, and certain financial interests of a spouse or dependent.” All good ideas, but unrelated to special prosecutor investigations.

FOR NOW.

So what’s going on?

In May 2017, President Trump fired FBI Director James Comey who had been investigating links between the Trump campaign and Russian officials. At that time there were charges pending against Trump’s former National Security Advisor, Michael Flynn.

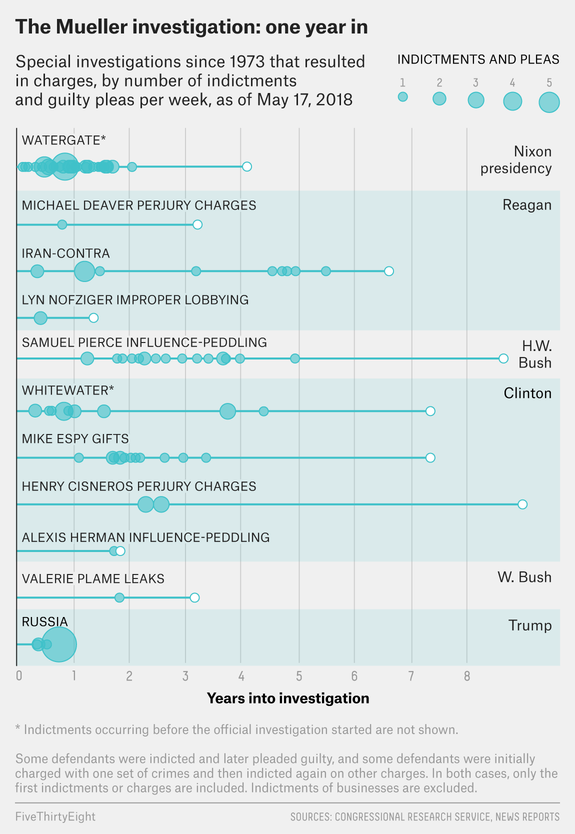

On May 17, 2017, Deputy Attorney General Rod Rosenstein authorized a special prosecutor to be appointed to investigate the role of the Russian government in influencing the 2016 Presidential election. Robert Mueller, lawyer and former director of the FBI, was appointed to take over the FBI investigation in the role of special prosecutor. Six hundred and seventy four days later, Mueller submitted his final report to Attorney General William Barr on March 22, 2019. In the course of his investigation, 34 people were indicted, seven U.S. nationals, 26 Russian nationals, one Dutch national, and three Russian organizations. Charges have been filed against Trump campaign members George Papadopoulos, Paul Manafort, Rick Gates, Michael Flynn, Michael Cohen, and Roger Stone.

In Barr’s letter to Congress regarding the Mueller report, he indicated that while there were clear efforts by the Russian government to influence the 2016 presidential election, there was not evidence that the president colluded with Russian officials. Mueller reached no conclusion on whether Trump obstructed justice, Barr quoted the special counsel as saying “while this report does not conclude that the President committed a crime, it also does not exonerate him.”

As of March 25, 2019, Attorney General Barr and Deputy Attorney General Rosenstein have yet to determine what, if any, of the report to release to Congress. Congress will then vote whether or not to make the report public.

Some Other Special Prosecutors and their Investigations

You’ve definitely heard about special prosecutors before because they always come with a presidential scandal. The first one was appointed in 1875 by Ulysses S. Grant to investigate the Whiskey Ring scandal (something about taxes and whiskey distillers and corruption, sounds cool but not the point right now). There were like 8 more after that (apparently everybody was bribing everybody else all the time) until we get to the Watergate investigation which 1) shaped how independent prosecutors and investigations were handled in the future and 2) is my favorite so I want to talk about it.

Watergate (155 days. 69 people charged. 1 Presidential resignation.)

[You can expect a much longer Watergate post in the future, but I’ll try to keep it short for now]

Basically, it was 1972, Richard Nixon was running for re-election, and 5 guys get arrested for breaking into the Democratic National Committee Headquarters inside the Watergate hotel. One of these guys has a bunch of crisp $100 bills and a White House employee in his address book. Then they find out that the Committee to Re-Elect the president deposited $25,000 in one of the burglar’s bank accounts and investigators start wondering how much illegal stuff the President’s friends were doing, and how much of it did he know about?

Nixon gets re-elected and he appoints Elliott Richardson as Attorney General, who promised in his Senate confirmation hearings that he would appoint a special prosecutor to look into the Watergate break-in. He picks Archibald Cox who was a lawyer and high up in the Justice Department when Kennedy was president. Cox starts investigating and finds out Nixon has been taping all of his conversations in the Oval Office (!!!) and subpoenas those tapes. Nixon says “what if I don’t?” and they both fight about it for a while til a Court of Appeals says Nixon has to turn over the tapes. So, because he is a mature adult, Nixon tells his Attorney General to fire Cox. Richardson says nope and resigns instead. Then Nixon asked told Deputy Attorney General William Ruckelshaus to do it, and he says nope and resigns too. Then the third in command, Solicitor General Robert Bork, who was not really okay with firing Cox but was kind of afraid democracy would fall apart if Nixon kept making people resign, finally fired Archibald Cox as special prosecutor. And all of that was on one Saturday night.

“Oh hell no.” – Richard Nixon

Then Nixon tried to say special prosecutors weren’t allowed anymore and people said “what?! Can you do that?!” and he said “fine” and had Bork appoint a new one named Leon Jaworski. Jaworski picked up where Cox left off and parallel to his investigation, the Senate had formed a separate committee to investigate presidential campaign activities, and between the two, a bunch of information came out that made Nixon look guilty of all kinds of stuff. The House of Representatives started the process of impeachment and Nixon resigned before they could actually impeach and convict him.

The Watergate independent counsel continued it’s investigation after Nixon left office. Jaworski resigned, Henry Ruth Jr took his place, then he resigned and Charles Ruff finally finished the report, but by then Gerald Ford had already pardoned Nixon for everything he might have done, so they never charged him with anything. The furthest they got was listing him as an “unindicted co-conspirator” with the people they actually charged.

One important part of the Watergate report outlined the question of whether a sitting president can even be charged with a crime like a regular person, and Jaworski determined that it wouldn’t hold up in court and that it was something best handled by Congress and impeachment if necessary. However, once a president is no longer president, he CAN be charged with crimes he committed before and during his presidency, but it’s never happened.

Iran-Contra (2,420 days. 14 people charged.)

It’s 1981, Ronald Reagan has just become the president. Jimmy Carter had issued sanctions against selling weapons to Iran because they took a bunch of Americans hostage in 1979. However, Reagan and a bunch of his senior administration officials decide they’d rather secretly sell weapons to Iran because that was better than Iran becoming friends with the Soviet Union and their weapons. Then the US went around telling everybody not to sell arms to Iran because they sponsored terrorists. (spoiler: this will look really bad later.)

Around the same time, some guys in Nicaragua decided to rebel against their government and called themselves Contras (short for la contrarrevolución, in English “the counter-revolution”.) Reagan was loudly in favor of the Contras, but Congress passed a bill to prevent the United States from providing them with any help because it was a Bad Idea(™).

In 1985, a guy from Reagan’s National Security Council decides it would be a great idea to kill two illegal birds with one illegal stone and use the money they made from selling arms to Iran to help out the Contras in Nicaragua. The whole situation was leaked to the press and in international levels of arrogance, entitlement, and hypocrisy, Reagan denied any wrongdoing.

“We didn’t do anything. And even if we did, it wasn’t illegal. Either way I know better than you so just let me do it. But I didn’t.” – Ronald Reagan

At the end of 1986, Lawrence Walsh was appointed special prosecutor and again, he investigated along side both House and Senate investigations. The congressional committees held hearings to gather evidence, and offered immunity to some key witnesses. Walsh’s investigation led to convictions of National Security Council members John Poindexter and Oliver North, but those convictions were overturned due to their immunity deals with Congress. The special prosecutor report did not find proof of Reagan’s involvement in the Iran-Contra affair and did not recommend any charges against him.

Whitewater and Monica Lewinsky (1,693 days. 1 impeachment.)

The investigation into Bill and Hillary Clinton’s involvement in a failed real estate investment back when he was Governor of Arkansas probably would’ve been the most boring investigation ever. However, the newly reauthorized Ethics in Government Act allowed for an incredibly broad investigative scope for the independent counsel, Kenneth Starr. He started with what happened to the money the Clintons and their friends had invested and lost to the Whitewater Development Corporation, then he looked into the death of White House counsel Vince Foster (turns out he killed himself), then some people getting fired from the White House Travel Office (Travelgate), misuse of FBI files (Filegate), something about a law firm, and then accusations of sexual harassment by Paula Jones, which led him to the Monica Lewinsky scandal. Along with being criminally bad at naming scandals, Kenneth Starr gave the impression that he was searching for any dirt on the Clintons, and in the course of his investigation was given taped conversations implicating Bill Clinton in a sex scandal.

In case you weren’t alive or conscious in 1998, while he was president, Bill Clinton had an inappropriate sexual relationship with a White House intern named Monica Lewinsky. Kenneth Starr’s position as independent counsel allowed him to pivot his investigation to whether Lewinsky received preferential treatment due to her relationship with the president, whether Clinton had lied under oath about the relationship, or if he had instructed her to lie under oath. Starr turned over his final report to Congress in September 1998, and Congress voted to release the full report to the public. Unlike Watergate and Iran-Contra, Congress did not hold separate investigations, and cited the Starr investigation when the House voted to impeach President Clinton on the charges of perjury and obstruction of justice. Clinton was tried in the Senate and acquitted of the charges and remained in office.

Sources

- A Guide to the Mueller Investigation for Anyone Who’s Only Been Paying Half-Attention (Splinter News, March 20, 2019) [my favorite source by far]

- Allegation Nation: A Brief History of Presidents and Special Prosecutors (Saturday Evening Post, May 11, 2017

- How Mueller’s First Year Compares To Watergate, Iran-Contra And Whitewater (FiveThirtyEight, May 17, 2018)

- Every report on past presidential scandal was a warning. Why didn’t we listen? (The Washington Post, March 22, 2019)

- Mueller’s Investigation Lasted 674 Days. Here’s How That Compares to Other Probes (Time, March 23, 2019)

- What Independent Investigations of the Past Can Teach Congress About Its Role in the Mueller Probe (Lawfare Blog/Brookings Institute, January 11, 2019)

- Special Counsel Investigations: History, Authority, Appointment and Removal (Congressional Research Service, March 13, 2019)

- Trump, Mueller and the lessons of history: Special prosecutors “are incapable of saving us” (Salon, January 20, 2019)

- From Robert Mueller to Kenneth Starr, a look at special prosecutors throughout history (Fox News, June 4, 2018)

- The fraught political history of special prosecutors (Politico, March 2, 2017)

- Whiskey, Watergate and Whitewater: How special prosecutor Robert Mueller’s predecessors made history (The Washington Post, March 19, 2019)

- Sam J. Ervin Papers (UNC Libraries)

- Watergate scandal (Wikipedia)

- Iran-Contra Affair (Wikipedia)

- Whitewater Controversy (Wikipedia)

- Impeachment of Bill Clinton (Wikipedia)

- Ethics in Government Act (Wikipedia)

- Special Counsel Investigation (2017-2019) (Wikipedia)